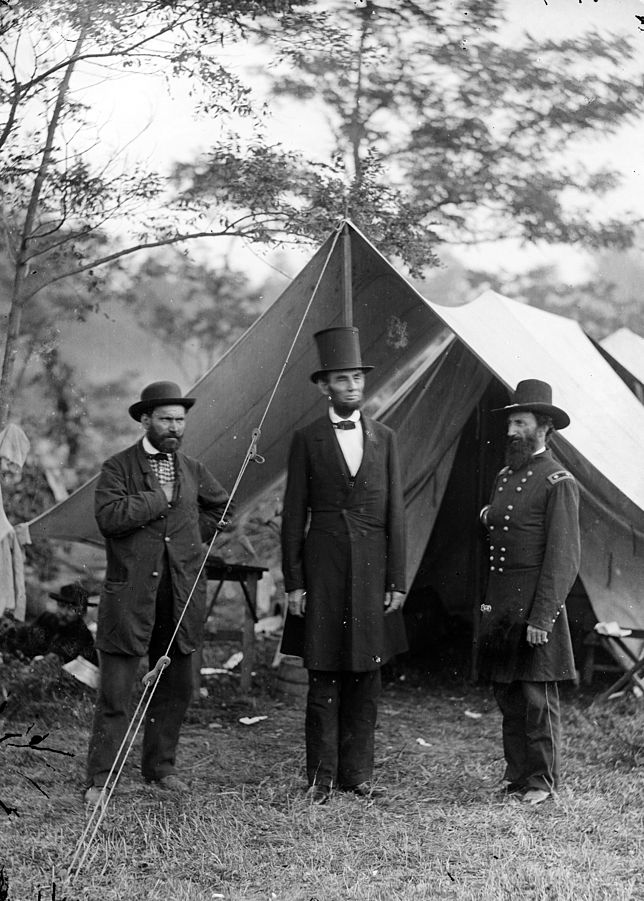

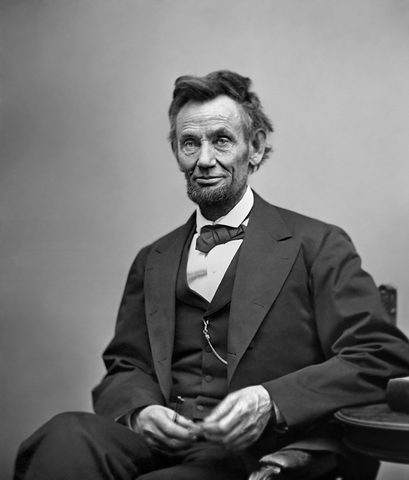

Allan Pinkerton, President Abraham Lincoln, and Major General John A. McClernand in this this photo taken not long after the Civil War’s first battle on northern soil in Antietam, Maryland on October 3, 1862. Lincoln and his administration supported restrictions on the press and free speech during the Civil War. (Photo via Wikimedia, public domain)

The federal government restricted constitutional liberties during the Civil War (1861–1865), including freedom of speech and freedom of the press.

Union generals took measures to prevent newspapers from publishing battle plans and to keep Confederate sympathizers from aiding the enemy by disseminating military information or discouraging enlistments.

At the time, President Abraham Lincoln’s political opponents argued that these measures went beyond those necessary to execute the war. Although historians have absolved Lincoln of charges that he restricted civil liberties for political gain, scholars continue to debate the constitutionality of Lincoln’s actions.

Throughout the war, newspaper reporters and editors were arrested without due process for opposing the draft, discouraging enlistments in the Union army, or even criticizing the income tax.

Handling dissent in the North presented an unprecedented difficulty for the Lincoln administration. From the start of Lincoln’s presidency, the Northern press gave voice to many of his critics. Newspapers argued that secession was the inevitable consequence of his policy toward the South. As the war dragged on, the opposition press grew louder, demanding compromise with the Confederacy to halt the bloodshed.

Fervent Union loyalists argued that dissent in the press amounted to treason. Citizens in the North wrecked “disloyal” newspapers in an effort to stymie pro-Southern sentiment.

In New York and New Jersey, two grand juries drew up presentments against newspapers that had been critical of the Union effort, which one paper called the “unholy war.” One grand jury presented a list of newspapers that encouraged the rebels, explaining, “The Grand Jury are aware that free governments allow liberty of speech and of the press to their utmost limits, there is, nevertheless, a limit. If a person in a fortress or an army were to preach to the soldiers submission to the enemy, he would be treated as an offender. Would he be more culpable than the citizen who, in the midst of the most formidable conspiracy and rebellion, tells the conspirators and rebels that they are right, encourages them to persevere in resistance and condemns the effort of loyal citizens to overcome and punish them as an ‘unholy war’?”

Seizing on the grand jury’s actions, federal officials in the Post Office Department in Washington ordered the postmaster of New York to cease mailing the publications on the grand jury’s list. Following the postmaster’s lead, U.S. marshals in Philadelphia seized copies of the listed newspapers as they arrived by train.

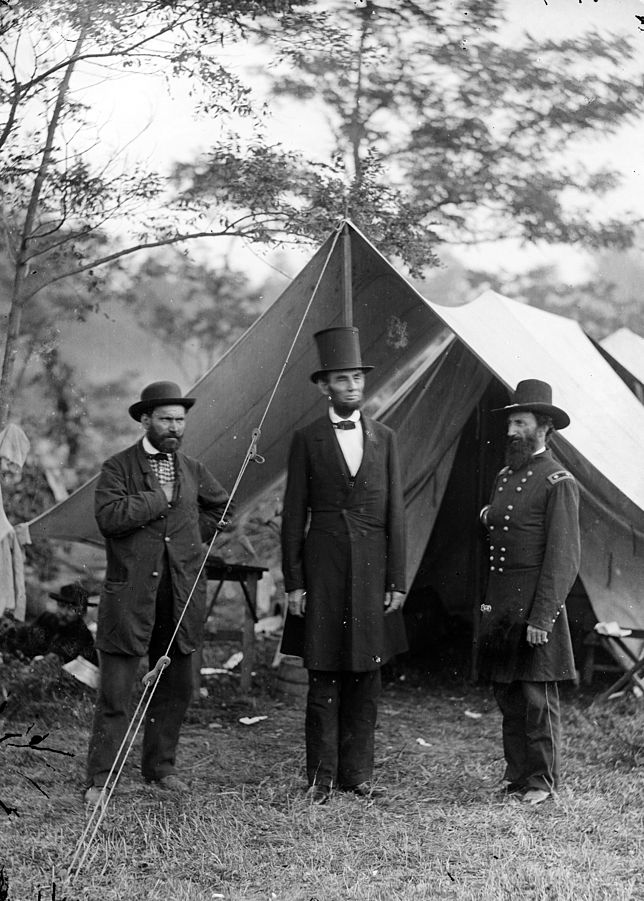

During the Civil War, in the vast majority of instances, the government restrained the free press without any legal process. The military routinely arrested newspaper editors and closed their presses; military tribunals banished some of them to the Confederacy for encouraging resistance. Secretary of State William Seward (above) ordered the arrest of an editor from the Freeman’s Journal for allegedly treasonous statements made in his newspaper. The government held the editor for 11 weeks before eventually releasing him without a trial. (Image via Library of Congress, public domain)

In the vast majority of instances, the government restrained the free press without any legal process.

The military routinely arrested newspaper editors and closed their presses; military tribunals banished some of them to the Confederacy for encouraging resistance.

In Canton, Ohio, a mob destroyed the offices of the Stark County Democrat after its editor, Archibald McGregor, published allegedly treasonous statements. When McGregor persisted, one year later, the army arrested him on unspecified charges. The city’s Republican postmaster accompanied the soldiers making the arrest, lending credibility to charges that the assault and arrest had been politically motivated.

Lincoln’s cabinet members, and sometimes Lincoln himself, ordered arrests:

Advancements in technology led to new types of censorship. The development of telegraph lines in the 1850s allowed reporters on the battlefield to provide near-contemporaneous accounts of strategies and troop movements. As the Civil War began in April 1861, the Lincoln administration censored telegraph dispatches to and from Washington.

Gen. George McClellan had initially gathered a group of Washington correspondents and reached an agreement on censorship of telegraph dispatches.

The House Judiciary Committee investigated the matter in December 1861 and issued a report stating that the government should not interfere with the transmission of telegraph communications “except when it may become necessary for the government, under the authority of Congress, to assume exclusive control of the telegraph for its own legitimate purpose.”

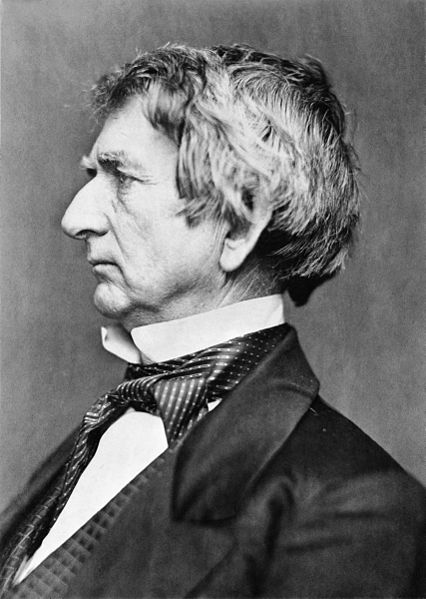

The Lincoln administration had good reason to be concerned about the press. Despite general prohibitions, soldiers regularly sought out and exchanged newspapers across enemy lines. Gen. William T. Sherman (above) had completely baffled Confederate general William Hardee with a series of feint troop movements around the Carolinas. When Gen. Hardee received a copy of the New York Tribune, he learned that Sherman’s supply ships were gathering at Morehead City, North Carolina. Sherman’s tactics were foiled, and the Union army suffered heavy losses in battle. This event supported Sherman’s view of war correspondents as spies for the enemy. (Image via Library of Congress, probably Matthew Brady circa 1865, public domain)

Lincoln sought to limit restrictions to those that served the military’s needs. His sensitivity was, at least in part, based on a desire to keep border states on the Union’s side, but also to rebut claims of exceeding his authority for political gain.

In 1863 Lincoln revoked Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s order suspending the Democratic Chicago Times, stating that he was “embarrassed” by his general’s failure to balance what was due to the Union on one hand and “the Liberty of the Press on the other.”

In other instances, Lincoln chastised Gen. John Schofield for arresting the editors of the Missouri Democrat and warned another general to refrain from suppressing newspapers unless he could ascertain “palpable injury to the Military in your charge.” Even as Lincoln believed that he would lose re-election in 1864, he refrained from measures that might unnecessarily restrict political dissent.

The Lincoln administration had good reason to be concerned about the press.

Despite general prohibitions, soldiers regularly sought out and exchanged newspapers across enemy lines. Confederate general Robert E. Lee kept apprised of movements by Gen. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac by reading Northern newspapers. In one instance, the pro-Union Philadelphia Inquirer published the position of McClellan’s maneuvers, unwittingly leading Lee to withdraw his troops from the defense of Richmond and put them on the line.

Later in the war, Gen. William T. Sherman had completely baffled Confederate general William Hardee with a series of feint troop movements around the Carolinas.

When Gen. Hardee received a copy of the New York Tribune, he learned that Sherman’s supply ships were gathering at Morehead City, North Carolina. Sherman’s tactics were foiled, and the Union army suffered heavy losses in battle. This event supported Sherman’s view of war correspondents as spies for the enemy.

The Lincoln administration restricted the ability of active Peace Democrats to speak out against the war. Prison records show numerous arrests for various offenses, including:

Union officers enforced general bans against items displaying Confederate mottoes or images.

In 1862 Lincoln issued a proclamation authorizing military trials for persons discouraging enlistments in the Union army.

Throughout the North, government authorities and the military arrested agitators without legal process for discouraging enlistment or making statements sympathetic to the South.

Some of those arrested included prominent critics of the administration, among them a former member of the U.S. House of Representatives imprisoned in Ohio. While jailed, the former representative was nominated and elected to the Ohio legislature.

Republicans quickly realized that imprisoning critics of the war could work to embolden the detainees’ message. After the Republicans lost seats in the congressional elections of 1862, Secretary Stanton issued an order releasing all persons who had been arrested for discouraging enlistments.

The most famous limitation on individual speech during the Civil War resulted from Burnside’s General Order No. 38, announcing that treason, “express or implied,” would not be tolerated. On May 1, 1863, former congressman Clement Vallandigham (above) gave a speech at a Democrat Party rally in which he openly disobeyed Burnside’s order. Vallandigham proceeded to call for the removal of “King Lincoln” and denounced the administration for not seeking an immediate and peaceful resolution to the war. When Burnside learned of Vallandigham’s speech, he ordered his detention. Vallandigham was sentenced to prison for the remainder of the war The Supreme Court denied review of the case in Ex parte Vallandigham (1863). (Image via Library of Congress, by Matthew Brady between 1855 and 1865, public domain)

The most famous limitation on individual speech resulted from Burnside’s General Order No. 38, announcing that treason, “express or implied,” would not be tolerated. The order proclaimed that “the habit of declaring sympathies for the enemy will not be allowed in this department” and that anyone violating the order would be imprisoned or “sent beyond our lines into the lines of their friends.”

On May 1, 1863, former congressman Clement Vallandigham gave a speech at a Democrat Party rally in which he openly disobeyed Burnside’s order. In fact, as he explained during the speech, he “despised it, spit upon it, and trampled it under his feet.”

Vallandigham — a nationally known Peace Democrat — proceeded to call for the removal of “King Lincoln” and denounced the administration for not seeking an immediate and peaceful resolution to the war.

When Burnside learned of Vallandigham’s speech, he ordered his detention.

On May 5, 1863, a company of soldiers arrested Vallandigham at his home. Burnside charged Vallandigham with “Publicly expressing, in violation of General Order No. 38… sympathy for those in arms against the Government of the United States, and declaring disloyal sentiments and opinions, with the object and purpose of weakening the power of the Government in its efforts to suppress an unlawful rebellion.”

Vallandigham appeared before a military tribunal, which found him guilty and sentenced him to prison for the remainder of the war. A federal circuit judge upheld Vallandigham’s arrest and military trial as a valid exercise of the president’s war powers.

The Supreme Court denied review of the case in Ex parte Vallandigham (1863). Concerned that General Burnside’s rash actions would turn Vallandigham into a martyr, Lincoln commuted the sentence from imprisonment to banishment to the Confederacy.

Lincoln defended this restriction by arguing,“Must I shoot a simple-minded soldier boy who deserts, while I must not touch a hair of a wily agitator who induces him to desert? I think that in such a case to silence the agitator and save the boy is not only constitutional, but withal, a great mercy” (Wilson 2006: 173–174).

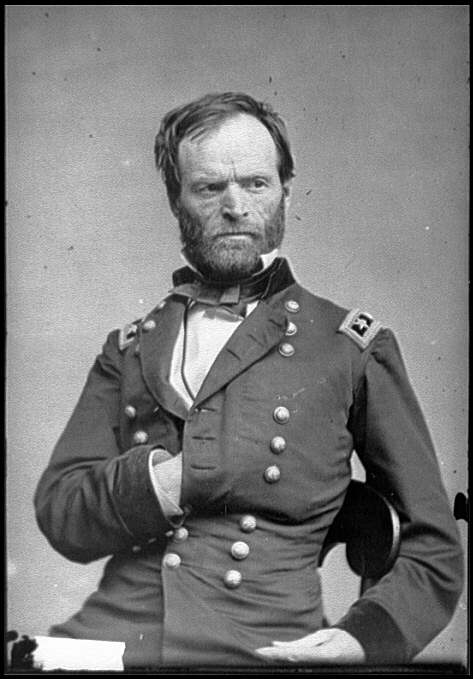

Scholars have labored to evaluate the Civil War administration’s actions in hindsight. The Constitution’s text does not provide a clear basis to condemn Lincoln’s actions. The First Amendment specifically prohibits Congress from making laws abridging freedom of speech” but Lincoln justified his actions restricting speech and the press based on the president’s war powers under the Constitution. The Supreme Court would not address application of the First Amendment until nearly half a century after the Civil War ended, so restrictions defined in the Court’s modern jurisprudence were at that time nonexistent. With respect to civil liberties, Lincoln presented a choice in a speech of July 1861: “Must a government of necessity, be too strong for the liberties of its own people, or too weak to maintain its own existence?” (Wilson 2006: 78). Under this choice, survival of the nation — as the foremost constitutional principle — took precedence over protections found in the First Amendment and other provisions in the Constitution. (Image via Library of Congress, by Alexander Gardner 1865, public domain)

Scholars have labored to evaluate the Civil War administration’s actions in hindsight. The Constitution’s text does not provide a clear basis to condemn Lincoln’s actions.

The First Amendment specifically prohibits Congress from making laws abridging freedom of speech” but Lincoln justified his actions restricting speech and the press based on the president’s war powers under the Constitution. The Supreme Court would not address application of the First Amendment until nearly half a century after the Civil War ended, so restrictions defined in the Court’s modern jurisprudence were at that time nonexistent.

Many scholars today look at Lincoln’s restrictions as a kind of necessary evil. They will typically explain that Lincoln probably violated the Constitution during the war, but forgive his infractions in light of the context and the result.

Other scholars argue that Lincoln’s defense of his actions reveals a constitutionally justifiable view of executive powers during wartime. Lincoln himself thought that the exigencies of war might justify actions that would otherwise be unconstitutional if necessary to preserve the nation.

Thus, with respect to civil liberties, Lincoln presented a choice in a speech of July 1861: “Must a government of necessity, be too strong for the liberties of its own people, or too weak to maintain its own existence?” (Wilson 2006: 78). Under this choice, survival of the nation — as the foremost constitutional principle — took precedence over protections found in the First Amendment and other provisions in the Constitution.